WASH and Gender: Impact Measurement and Management

- projectmaji

- Sep 30, 2025

- 3 min read

As is well studied, women and girls are disproportionately affected by water poverty, as they face heightened security risks, limited economic opportunities, and decreased education rates. A recent study commissioned by the Impact-Linked Fund for WASH (co-designed by Aqua for All and Roots of Impact) explored the nexus between WASH and gender to produce measurable indicators for gender-related outcomes. Project Maji was pleased to contribute our own database to researchers Rahul Ranjan Sinha and Nikita Tulsyan for this study. The brief, “Strengthening Impact Measurement and Management (IMM) at the WASH and Gender Nexus”, offers actionable guidance to WASH enterprises, funders, and investors on gender mainstreaming and IMM approaches.

Mapping Gender Impact in WASH

Based on the contributions of 11 enterprises across Africa and Asia, the study reveals 6 main gender outcomes of WASH interventions:

However, context-specific dynamics including geography, customer demographics, and cultural norms determine which gender outcomes are most relevant for a particular enterprise. For example, in the case of Project Maji, as we serve remote areas with poor infrastructure, time savings are typically more pronounced across all our sites, while a factor like safety depends heavily on individual context. The study encourages funders and enterprises alike to apply a SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound) framework for defining metrics that are field-tested, recognised as reliable, and aligned with existing standard sector practices.

On the matter of contextual conditions for gender outcomes in WASH, the research advocates for:

Pre-intervention practices: understanding the community before any intervention, to allow for an examination of gender engagement with WASH services. Such insights provide a baseline for the design of relevant interventions and tracking meaningful change.

Geography: Environmental factors and landscape affect access to and the reliability of WASH services. Enterprises should be conscious of elements like weather patterns and terrain, as they may deepen the risks associated with water collection, which primarily falls to women and girls.

Socio-cultural factors: Cultural values and gender norms shape the experiences of community members in relation to WASH practices. Gender-based violence during collection, taboos surrounding menstruation, and the ability of female members to participate in programmes, are among the dynamics that need to be addressed for effective gender-responsive WASH interventions.

Institutional factors: Governance structures, community organisation, and other service providers, may also influence gender outcomes.

Best Practices

“For Impact-Linked Finance transactions (or other results-based mechanisms with short-to medium-term timelines), enterprises should prioritise measuring gender outcomes that are likely to emerge in the short- and medium-term and using SMART metrics that are both context-sensitive and sector-validated.” (Source)

Best practices for gender outcome measurement are:

Use standardised and field-tested indicators

Collect disaggregated data

Apply gender sensitivity in data collection

Conduct a comprehensive gender analysis at baseline

Tailor indicators to enterprise contexts

Prioritise key user- and gender-level data points

Reflections

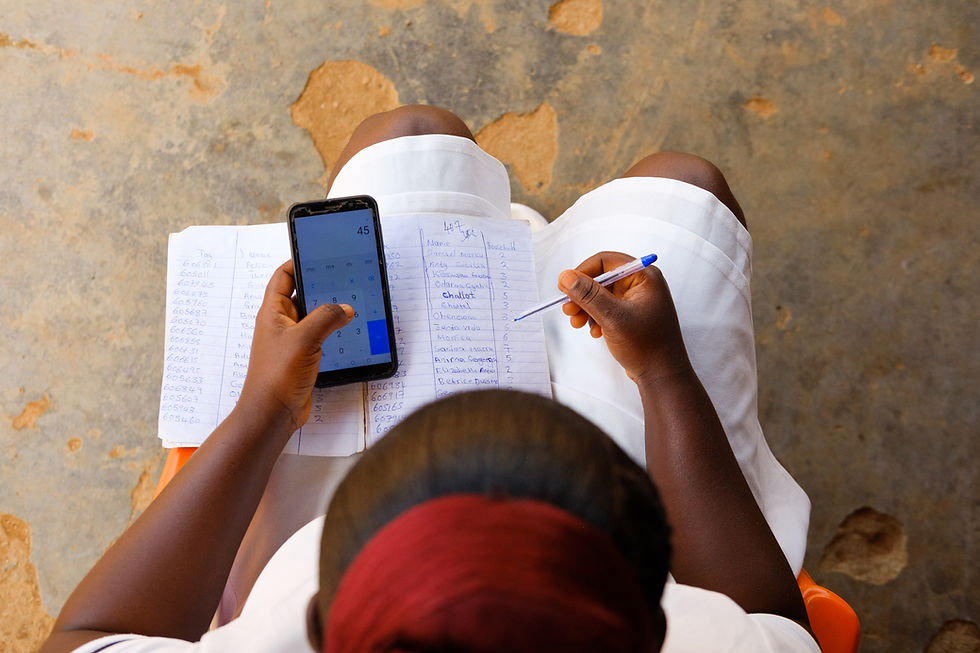

Many of Project Maji’s methods and understandings have been reflected in this piece of research. For example, conducting pre-impact surveys to accurately gauge individual relationships to WASH matters is an integral part of our pre-intervention phase. It identifies the key concerns of community members, as well as general trends regarding gendered experiences of WASH. Establishing this baseline prior to water kiosk installation then allows us to accurately study the effects of safe water access, including whether the concerns of women and girls are being adequately addressed. Just as outlined in the paper, Project Maji focuses on tracking immediate and observable changes (such as reduced water collection time), rather than long-term systemic change.

The takeaways are not solely for IMM efforts of WASH enterprises, but apply to funders interested in Impact-Linked Finance as well. WASH funders should be conscious about building capacity for gender-responsive programmes, incorporating gender indicators into impact indicators, and scaling up after piloting and stakeholder feedback.

What is important for both enterprises and funders to understand is that WASH solutions generally contribute rather than directly cause structural outcomes. Systemic change takes time, includes a myriad of factors unlikely to be delivered solely by WASH solutions, and is difficult to measure directly within short project cycles. Still, the research shows that WASH enterprises do and can continue to play a catalytic role in advancing gender equality.

Read the full brief here.